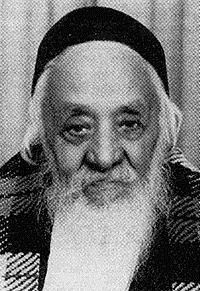

A Short Tribute

Mori Amram Korach, son of Mori Yihya Korach, was born on 7 Sivan, 5631 (1871) in Sana'a, Yemen. He began his Torah studies with his father, one of Yemen's greatest sages of the time, but when he was only 10 years of age, his father died; he continued his studies with Mori Haim Korach.

His first public position was as a scribe in Mori Sleiman Karra's rabbinic court. He was then appointed to be in charge of the community trust fund and also served as Rabbi of the Alexandria Synagogue in Sana'a.

In 1932 he was chosen as the assistant of Yemen's Chief Rabbi, Mori Yihya Avitch; in 1934, he was appointed as Chief Rabbi of Yemen's Jews. His wisdom and knowledge of Islamic culture served him well in his contacts with Yemen's Muslim authorities, in particular as concerned tax collection and the community leadership's exchanges with the authorities.

On Yom Kippur Eve of 1950, he immigrated to Israel, with the majority of the Yemenite Jewish community, through Operation Eagle Wings. He lived out his last years in Israel, which he termed the Revival of Redemption.

Mori Amram Korach passed away on 14 Tishrei, 5713 (1953) and was buried in Jerusalem. His grandson, Rabbi Shlomo Korach, is currently Chief Sephardi Rabbi of the city of Bnei Brak.

Mori Amram Korach had three books published: Sa'arat Teiman – customs of Yemenite Jews and descriptions of their lifestyles, 'Almot Shir – a commentary on some 200 piyuttim (sung liturgical poetry) from the Diwan (collection of poetry) and Neveh Shalom – a commentary on Rabbi Saadia Gaon's tafsir (exegesis) of the Bible.