A Short Tribute

Hacham Joseph Ergas was born to Sarah and Hacham Emanuel in 1685, in Livorno, Italy. He learned Torah from his father, who was one of the city's sages, and studied in the yeshiva headed by the Rabbi of Livorno, Hacham Samuel De Pas. In 1704 he married Sarah, daughter of Abraham Miranda, and the couple had three sons and three daughters.

Hacham Joseph Ergas moved to the city of Raggio, where he studied Kabbala with kabbalist Hacham Binyamin Hacohen, Hacham Moshe ZAkut's student. He later moved to Pisa, where he founded the Neve Shalom yeshiva and several charitable institutions. Upon his return to Livorno, he was acclaimed by the community and began to officiate as its rabbi. He raised many students, including Hacham Malachi Hacohen, author of Yad Malachi, and his two sons - Hacham Emmanuel, who succeeded him as the city's rabbi, and Hacham Abraham, who published his numerous books.

His Kabbalistic thought proposed an explanation of the HAAR"I's theory of tsimtsum as a parable היוצא מידי פשוטו and was the scholarly opponent of his cousin, who also lived in Livorno, kabbalist Hacham Emmanuel Hai Ricci, author of Mishnat Hassidim.

In 1710, Hacham Nehemiah Hiya Hayoun, suspected of Shabbetaism, arrived in Livorno. Hacham Joseph Ergas opposed him until he was expelled from the city. Hacham Nehemiah Hiya Hayoun moved to Amsterdam, where he published a book of diatribe against him; Hacham Joseph Ergas wrote two books in rejoinder, Tochakhat Migolah and HaTzad Nakhash, published in 1715.

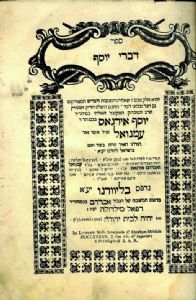

Hacham Joseph Ergas passed away in Livorno on 3 Sivan, 5490 (1730) at the age of 45. Among his writings one counts Shomer Emunim – an introduction to Kabbala, Divrei Yoseph – Responsa, Minkhat Yosef – on Kabbala, and Mevo Petakhim – on the HAAR"I's thought.

A few quotes from the Rabbi on 'Torah Study' in which he teaches that not all intellects are identical, and that one should teach students to ask questions themselves

One should study word by word with students, to each according to their level and ability. One should present a bright countenance, and not be stringent and become angry at their lack of knowledge or limited understanding and achievements, for not all intellects are identical. Even if one feels that they should have understood after two or three [explanations], they may not have understood because of the issue's complexity, or because of their ability to understand at that opportunity, for opportunities are not all identical. One should, instead, speak to them gently, comforting them with appeasing words, until one has made certain that their delay in understanding is the result of a lack effort and that their attention is not on the matter at hand but has been distracted. Then it is appropriate to show annoyance, until they are prepared to pay attention.

And when they ask a question about a difficulty, one should reply graciously, display pleasure towards their question, and encourage them to question, so that they open their hearts to Torah. If they refrain from asking, even when an issue seems not to have any explanation, they are likely not to ask about other issues - even when they do have explanations, and will be left with a law or halakha lacking sufficient reason or known explanation, like birds chirping. On the contrary; when they do not ask about a halakhic issue, one should act annoyed about how the question found in that halakha did not arise in their minds. One should show them the way to ask the questions themselves in the future, for is a person encounters a question, that person is close to understanding the matter, because a question is half the explanation. This way they will improve in their studies and, with God's help, greatly succeed.

Minhat Yoseph, p. 11a, section 56, Yaakov Tobiana Press, Livorno, 1827